Brainless jellyfish and sea anemones reveal sleep’s ancient origins in DNA repair

Sleep may have evolved far earlier than scientists once believed. New research shows that even brainless creatures like jellyfish and sea anemones experience sleep-like states. These findings suggest that restful periods, akin to good sleep hygiene, could have emerged in the simplest nervous systems over 600 million years ago.

The study also reveals that sleep in these animals serves a vital function: repairing DNA damage in neurons. This challenges the idea that sleep is a complex trait linked only to advanced brains.

Cnidarians, a group including jellyfish and sea anemones, display clear sleep patterns despite lacking a brain. Jellyfish sleep for about eight hours a day, mostly at night and during midday. Sea anemones, on the other hand, rest primarily in daylight. Their sleep is not controlled by consciousness—instead, researchers measure it by drops in muscle contraction frequency.

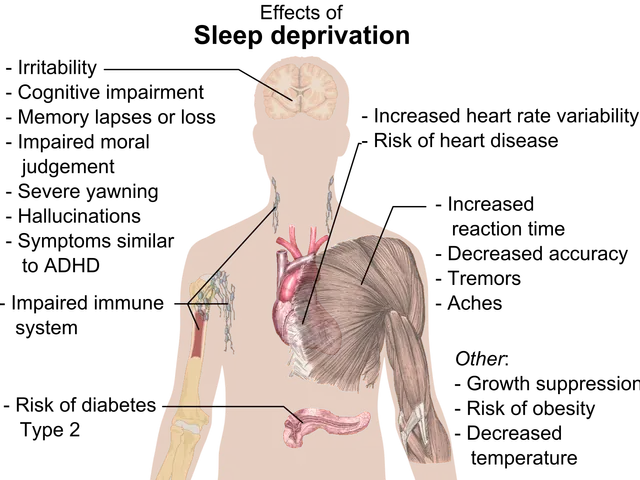

Light plays a key role in jellyfish sleep, while sea anemones rely on an internal clock. Both species produce melatonin, a hormone that regulates sleep in vertebrates. This shared trait hints at an ancient origin for sleep mechanisms, long before brains evolved. Experiments showed that sleep helps these animals repair DNA damage in their neurons. When exposed to UV radiation, they slept more to recover. If sleep was interrupted, DNA damage built up. This suggests that sleep first evolved as a way to protect and restore neural cells, with other benefits like learning and memory coming later. Some cnidarians can even show basic learning behaviours, though they lack complex brains. This supports the idea that sleep's role in memory might be older than previously assumed. Other animals, such as macaques, rats, dogs, tits, and turtles, also demonstrate learned behaviours—from avoiding poisoned food to remembering tasks years later—but cnidarians prove that even primitive nervous systems benefit from rest.

The discovery of sleep in brainless animals reshapes our understanding of its origins. Instead of being a feature of advanced life, it likely began in early neural networks as a way to repair DNA. This research also opens questions about whether simple learning and memory processes could have emerged alongside sleep in the earliest stages of animal evolution.