Cruise Sailing with Flat-Earthers

In the complex world we live in, human decision-making often seems a puzzle, filled with impulsive choices, self-deception, and poor foresight. But these tendencies, it turns out, are deeply rooted in our evolutionary past and reflect adaptive reasoning strategies that helped our ancestors survive and thrive.

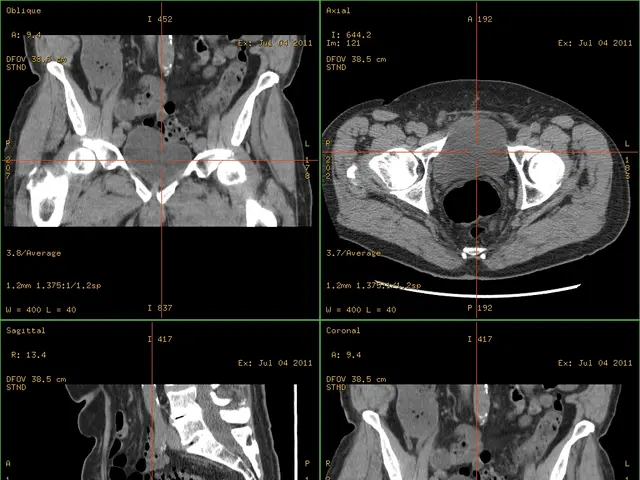

Research indicates that our brains process thoughts and decisions using two distinct, though interconnected, systems. The first system, an older evolutionary development, is primarily connected to the amyggdala, cerebellum, and basal ganglia, and governs quick, automatic responses. This system can provide instantaneous evaluations based on experience, which is preferable when decisions have to be taken immediately or are based on a large number of variables.

On the other hand, the second system is a relatively recent evolutionary development and governs deliberate actions based on careful evaluation of contextual information. Primarily connected to the prefrontal cortex, it offers the wonders of science and any choice based on reasoned arguments, especially when faced with a new problem. However, neither system has definitive control over the other, and mutual interferences between intuitions and reflections are imperfect.

Our evolutionary inertia is rooted in our ancestors who had to make fast decisions about food, threats, and reproduction, leading to a compromise between speed and accuracy. This compromise has resulted in our tendencies toward impulsive choices, self-deception, and poor foresight.

One such example of these adaptive features is positive illusions and self-deception. By overestimating our abilities or maintaining an optimistic view of reality, we increase our courage, ambition, and resilience, which in turn improve resource acquisition and reproductive success by motivating us to confront challenges rather than succumb to despair.

Cognitive biases, including impulsivity and poor foresight, can be understood in terms of bounded rationality and adaptive bias. Our ancestors operated with limited information and needed to make fast, cost-effective decisions based on heuristics and emotional shortcuts rather than exhaustive optimization. These shortcuts, like attribute substitution and selective attention, helped reduce cognitive load and improve survival chances in uncertain and time-constrained environments.

The brain’s cognitive system actively filters and reconstructs information selectively, favoring adaptive goals such as short-term survival and long-term development goals. This means what appears as poor foresight or self-deception may actually be an evolved cognitive strategy to balance immediate needs against future uncertainties.

Despite knowing we are wrong, we often make mistakes due to a deeper evolutionary logic that forces us to maintain our beliefs to avoid changing. We are belief machines, manufacturing beliefs that provide comfort or help us make sense of a chaotic world, even if they are irrational.

However, understanding these tendencies is the first step towards overcoming them. The only true antidote to falling back into "inhumanism," according to Levi, is critical and self-critical rationalism. This approach encourages us to distrust all the prophets that manipulate the imperfections of the human mind and strive for a more rational, informed decision-making process.

In conclusion, while humans may exhibit tendencies towards impulsive choices, self-deception, and poor foresight, these are byproducts of adaptive reasoning shaped by natural selection. They helped humans manage threats and compete successfully in complex environments by promoting psychological resilience, motivation, and efficient decision-making under uncertainty, even if they sometimes lead to suboptimal choices in modern contexts where conditions have changed dramatically.

- The second system, primarily connected to the prefrontal cortex, offers not only the wonders of science and deliberate actions, but also the potential for improved health-and-wellness, particularly in terms of mental-health, by encouraging a more rational, informed, and self-critical approach to decision-making.

- Understanding that our tendencies towards impulsive choices, self-deception, and poor foresight are deeply rooted in our evolutionary past and reflect adaptive reasoning strategies, we can strive to exercise mental-health practices that promote critical and self-critical rationalism, thereby overcoming these tendencies and making healthier decisions for our overall well-being.