Scientists build living computers from brain cells and synthetic biology

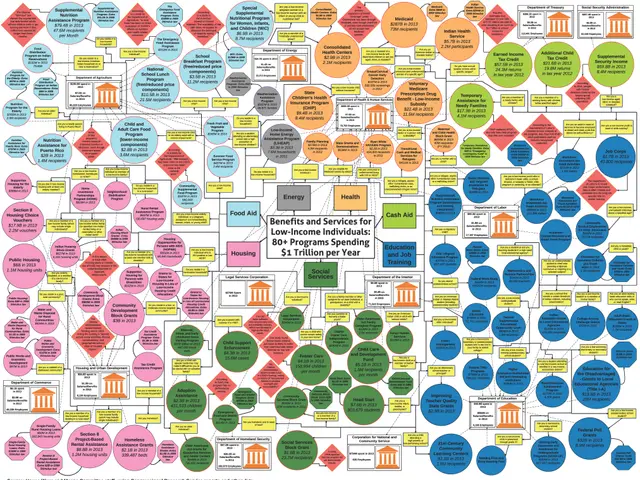

Scientists are developing biological computing systems that mimic learning and decision-making. These advances include brain organoids showing adaptable behaviour and synthetic cells performing complex tasks. The research blends biology with technology, opening new possibilities for biocompatible computing and medical applications.

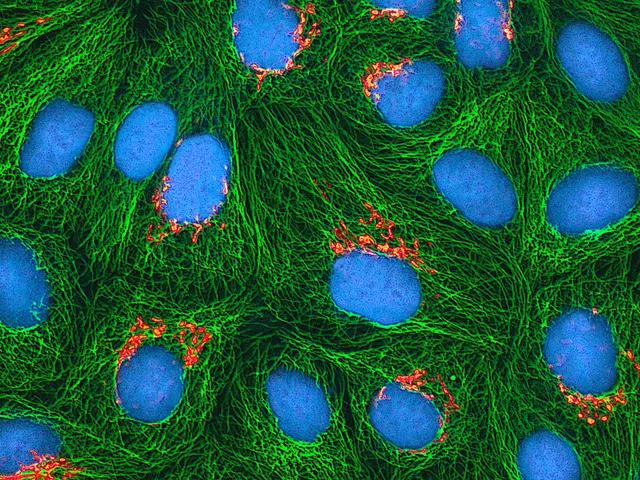

Human brain organoids have demonstrated basic learning-like responses in recent experiments. When exposed to controlled stimulation, they altered their neural connections and gene activity. This suggests the presence of biological mechanisms that can adapt and process information, much like simple computing hardware.

Researchers have also engineered protein circuits inside mammalian cells that function like decision-making networks. A team at Caltech built a system where proteins balance self-activation and mutual inhibition, ensuring only the strongest input triggers a response. This mimics a 'winner-take-all' process, converting noisy signals into clear actions.

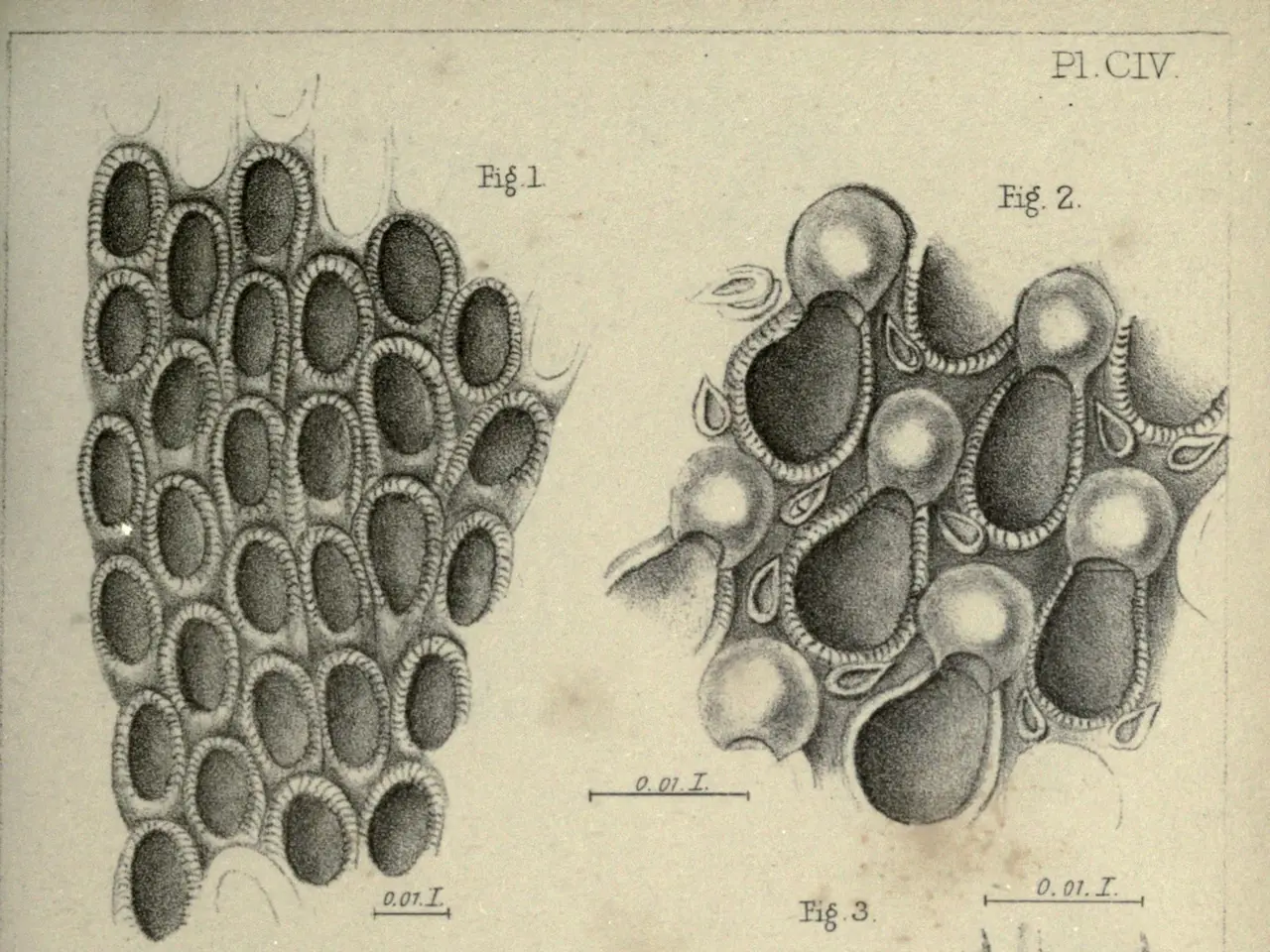

Meanwhile, simpler synthetic cells—called protocells—have shown early signs of decision-making. One experiment involved a protocell made of lipids and proteins that sensed chemical gradients and reshaped itself. This behaviour mirrors how living cells prepare to move, hinting at primitive problem-solving abilities.

Chemical processes, too, are being harnessed for computing. The formose reaction, a prebiotic process, has been used to classify inputs and predict patterns without traditional electronics. This approach could lead to chemical-based 'reservoir computers' that operate in biological environments.

Leading institutions like Harvard, MIT, and ETH Zurich have pushed these boundaries further. Harvard's 2024 study in Science showed how engineered bacteria could classify signals using protein networks. MIT's 2025 work in Nature Chemistry demonstrated chemical networks that distinguish complex molecular inputs. These developments point toward hybrid systems where biological components handle sensing while silicon manages coordination.

The research combines brain organoids, protein circuits, and synthetic cells to create adaptive, biocompatible computing. These systems could eventually be used in neural repair, tactile sensors, or edge computing within living organisms. The next step involves integrating biological and electronic components into functional hybrid architectures.