Scientists uncover brain circuits that control hunger and obesity breakthroughs

Scientists have discovered two opposing brain circuits that regulate hunger and satiety in mice. One pathway inhibits feeding in well-fed animals, while the other drives food-seeking behavior during fasting. These findings may revolutionize the treatment of obesity and appetite disorders.

Meanwhile, a novel drug combining three gut hormones is being tested to achieve significant weight loss—without surgery or its risks.

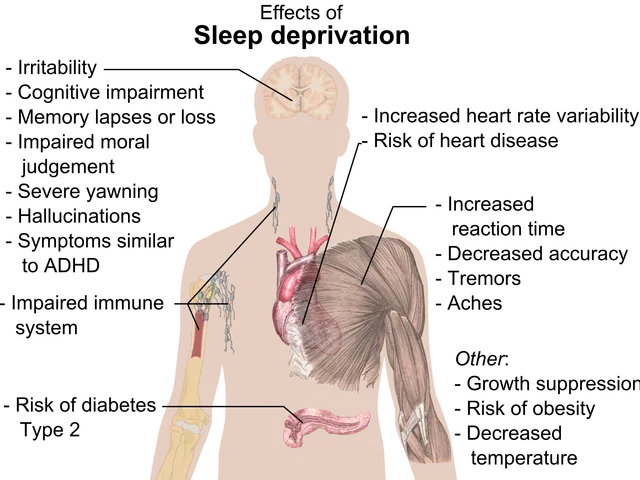

Researchers identified the two circuits by stimulating specific brain regions in mice. Activation of one circuit immediately stopped eating in well-fed animals. Mice lacking this circuit gained weight steadily, indicating it acts as a natural brake on overeating.

During fasting, the hunger pathway became more sensitive, while the satiety circuit weakened. This shift explains why animals—and potentially humans—struggle to resist food when hungry. However, experiments with an optical neural chip revealed an unexpected finding: normal dopamine levels had little impact on the striatum, the brain's reward center. Only when dopamine was artificially boosted to over five times its baseline did eating behavior change significantly.

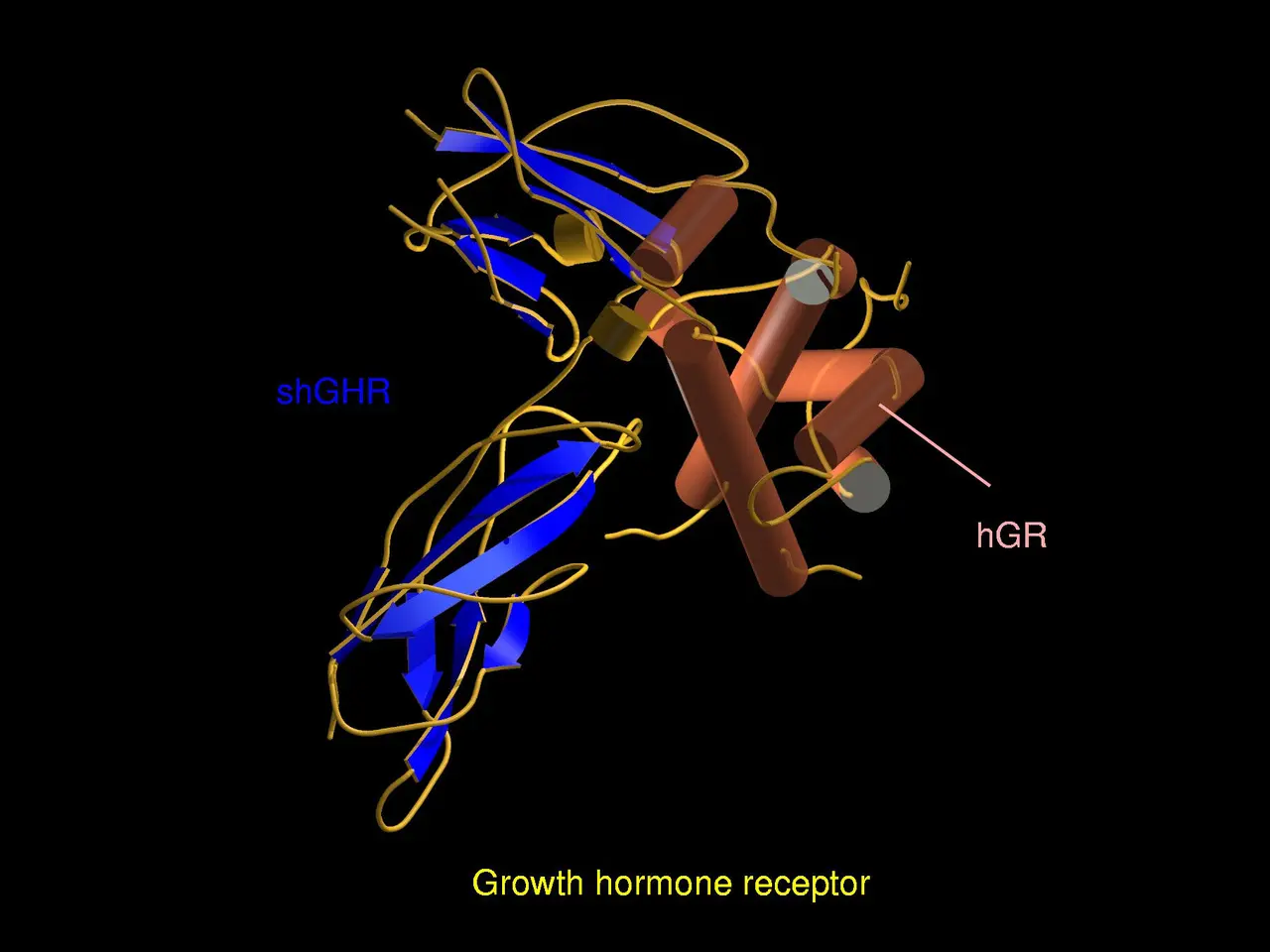

At Tufts University, a team led by Krishna Kumar is developing a drug that mimics the effects of bariatric surgery. The treatment combines three hormones: GLP-1, which suppresses appetite and slows digestion; GIP, which enhances insulin release and glucose control; and glucagon, which burns fat and increases energy use. Early tests suggest it could achieve a 30 percent weight loss—matching surgical results but without invasive procedures or their complications.

The discovery of these brain circuits provides a clearer understanding of how hunger and satiety are regulated. If the hormone-based drug proves successful in trials, it could offer a non-surgical alternative for obesity treatment. Together, these advances may lead to more effective therapies for weight-related diseases in the future.