UK's Stop and Search Powers Spark Debate Over Fairness and Human Rights

Stop and Search (S&S) powers remain a key tool for British police in maintaining public safety. These measures, governed by laws like the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 (PACE), aim to prevent crime and protect communities. Yet their use has sparked ongoing debates about fairness, racial bias, and the balance between security and human rights.

The primary legal framework for S&S comes from PACE, which requires officers to have reasonable suspicion before conducting a search. This suspicion must be genuine, based on observable facts, and objectively justifiable. However, broader powers exist under other laws.

Section 60 of the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994 (CJPOA) allows police to carry out searches without suspicion in designated areas if they believe serious violence may occur. Since its introduction, this power has been used increasingly, often targeting ethnic minorities, protesters, and young people at events like raves or demonstrations. Critics argue this has led to racial profiling and a loss of trust in policing.

By contrast, Section 47A of the Terrorism Act 2000 (TACT) imposes stricter conditions. It requires reasonable suspicion of a specific terrorist act, not just a general threat. This power is used less often, mainly at ports and borders, but still raises concerns about human rights and state overreach. The European Court of Human Rights reinforced these concerns in the Gillan case, ruling that S&S must comply with Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights—meaning searches must be lawful, necessary, and proportionate.

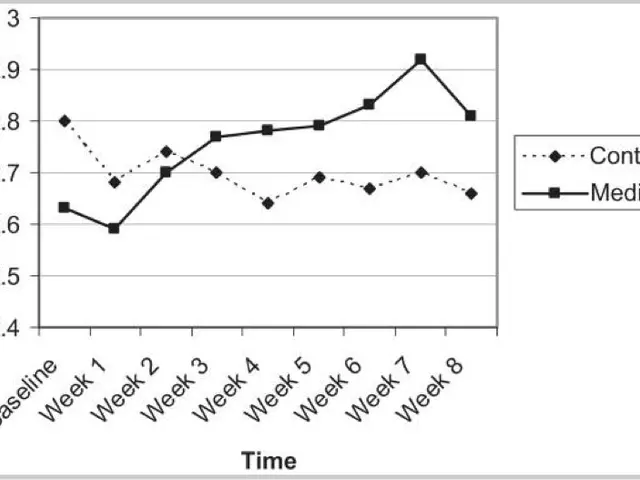

Research shows that when S&S disproportionately affects minority or disadvantaged groups, it can damage police legitimacy. If communities perceive these powers as unfair or discriminatory, cooperation with law enforcement often declines.

The tension between effective policing and protecting human rights remains unresolved. Current laws allow both suspicion-based and suspicionless searches, but their application continues to face scrutiny. Calls for reform highlight the need for policies that maintain security while ensuring fairness and public trust in the justice system.